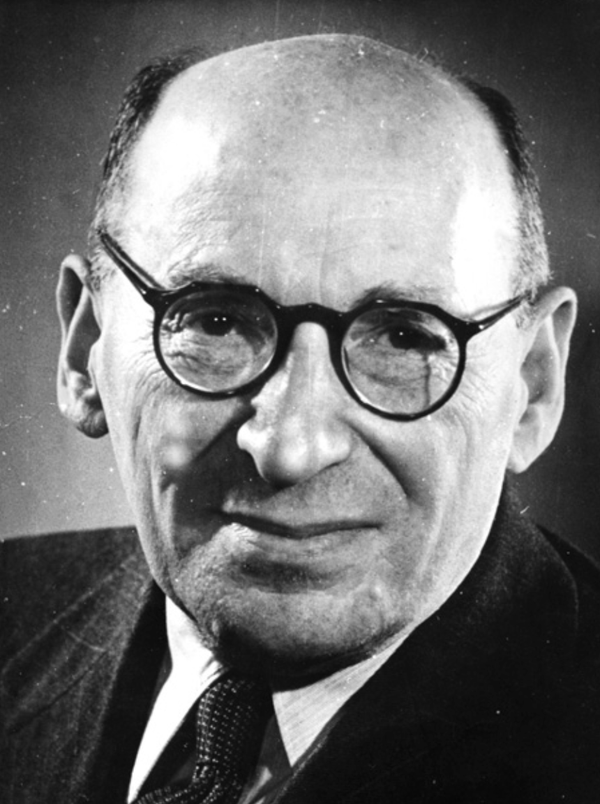

Hans Reichenbach, § 38 O problema da indução

Arquipélago

O texto a seguir é a seção 38 de Experience and prediction: An analysis of the foundations and the structure of knowledge (1938), escrito por Hans Reichenbach e traduzido por Gilson Olegario da Silva (UFRGS).

So far we have only spoken of the useful qualities of the frequency interpretation. It also has dangerous qualities. |

Até agora falamos apenas das qualidades úteis da interpretação frequentista. Ela também possui qualidades perigosas. |

The frequency interpretation has two functions within the theory of probability. First, a frequency is used as a substantiation for the probability statement; it furnishes the reason why we believe in the statement. Second, a frequency is used for the verification of the probability statement; that is to say, it is to furnish the meaning of the statement. These two functions are not identical. The observed frequency from which we start is only the basis of the probability inference; we intend to state another frequency which concerns future observations. The probability inference proceeds from a known frequency to one unknown; it is from this function that its importance is derived. The probability statement sustains a prediction, and this is why we want it. |

A interpretação frequentista desempenha duas funções na teoria da probabilidade. Primeiro, uma frequência é usada como uma substanciação para enunciados de probabilidade; fornece a razão pela qual acreditamos no enunciado. Em segundo lugar, uma frequência é usada para a verificação de enunciados de probabilidade; isto é, fornece o significado da afirmação. Essas duas funções não são idênticas. A frequência observada a partir da qual partimos é apenas a base da inferência de probabilidade; pretendemos determinar outra frequência que trate de observações futuras. A inferência de probabilidade parte de uma frequência conhecida para uma desconhecida; é dessa função que deriva sua importância. O enunciado de probabilidade sustenta uma previsão, e é por isso que o queremos. |

It is the problem of induction which appears with this formulation. The theory of probability involves the problem of induction, and a solution of the problem of probability cannot be given without an answer to the question of induction. The connection of both problems is well known; philosophers such as Peirce have expressed the idea that a solution of the problem of induction is to be found in the theory of probability. The inverse relation, however, holds as well. Let us say, cautiously, that the solution of both problems is to be given within the same theory. |

É o problema da indução que aparece com esta formulação. A teoria da probabilidade envolve o problema da indução, e uma solução do problema da probabilidade não pode ser dada sem uma resposta à questão da indução. A conexão entre ambos é bem conhecida; filósofos como Peirce expressaram a ideia de que uma solução para o problema da indução deve ser encontrada na teoria da probabilidade. A relação inversa, no entanto, também vale. Digamos, com cautela, que a solução de ambos os problemas deve ser dada dentro da mesma teoria. |

In uniting the problem of probability with that of induction, we decide unequivocally in favor of that determination of the degree of probability which mathematicians call the determination a posteriori. We refuse to acknowledge any so-called determination a priori such as some mathematicians introduce in the theory of the games of chance; on this point we refer to our remarks in §33, where we mentioned that the so-called determination a priori may be reduced to a determination a posteriori. It is, therefore, the latter procedure which we must now analyze. |

Ao unir o problema da probabilidade com o da indução, decidimos inequivocamente a favor daquela determinação do grau de probabilidade que os matemáticos chamam de determinação a posteriori. Recusamo-nos a reconhecer qualquer assim chamada determinação a priori, como alguns matemáticos introduzem na teoria dos jogos de azar; neste ponto remetemos às nossas observações da §33, onde mencionamos que a chamada determinação a priori pode ser reduzida a uma determinação a posteriori. É, portanto, este último procedimento que devemos agora analisar. |

|

By “determination a posteriori” we understand a procedure in which the relative frequency observed statistically is assumed to hold approximately for any future prolongation of the series. Let us express this idea in an exact formulation. We assume a series of events \(A\) and \(\overline{A}\) (non-A); let \(n\) be the number of events, \(m\) the number of events of the type \(A\) among them. We have then the relative frequency |

Por “determinação a posteriori” entendemos um procedimento no qual a frequência relativa observada estatisticamente é considerada aproximadamente para qualquer prolongamento futuro da série. Vamos expressar essa ideia em uma formulação exata. Assumimos uma série de eventos \(A\) e \(\overline{A}\) (não-A); seja \(n\) o número de eventos, \(m\) o número de eventos do tipo \(A\) entre eles. Temos então a frequência relativa |

|

\( h^n = \frac{m}{n} \) |

\( h^n = \frac{m}{n} \) |

|

The assumption of the determination a posteriori may now be expressed: |

A suposição da determinação a posteriori pode agora ser expressa: |

|

For any further prolongation of the series as far as \(s\) events (\(s > n\)), the relative frequency will remain within a small interval around \(h^n\); i.e., we assume the relation |

Para qualquer prolongamento adicional da série até \(s\) eventos (\(s > n\)), a frequência relativa permanecerá dentro de um pequeno intervalo em torno de \(h^n\); ou seja, assumimos a relação |

|

\( h^n - \epsilon \leqq h^s \leqq h^n + \epsilon \) |

\( h^n - \epsilon \leqq h^s \leqq h^n + \epsilon \) |

|

where \( \epsilon \) is a small number. |

onde \( \epsilon \) é um número pequeno. |

This assumption formulates the principle of induction. We may add that our formulation states the principle in a form more general than that customary in traditional philosophy. The usual formulation is as follows: induction is the assumption that an event which occurred \(n\) times will occur at all following times. It is obvious that this formulation is a special case of our formulation, corresponding to the case \(h^n\) = 1. We cannot restrict our investigation to this special case because the general case occurs in a great many problems. |

Esta suposição formula o princípio da indução. Podemos acrescentar que nossa formulação enuncia o princípio de uma forma mais geral do que a habitual na filosofia tradicional. A formulação usual é a seguinte: indução é a suposição de que um evento que ocorreu \(n\) vezes ocorrerá em todos os momentos seguintes. É óbvio que esta formulação é um caso especial de nossa formulação, correspondendo ao caso \(h^n\) = 1. Não podemos restringir nossa investigação a este caso especial porque o caso geral ocorre em muitos problemas. |

The reason for this is to be found in the fact that the theory of probability needs the definition of probability as the limit of the frequency. Our formulation is a necessary condition for the existence of a limit of the frequency near \(h^n\); what is yet to be added is that there is an \(h^n\) of the kind postulated for every \(\epsilon\) however small. If we include this idea in our assumption, our postulate of induction becomes the hypothesis that there is a limit to the relative frequency which does not differ greatly from the observed value. |

A razão para isso deve ser encontrada no fato de que a teoria da probabilidade precisa da definição de probabilidade como o limite da frequência. Nossa formulação é uma condição necessária para a existência de um limite de frequência próximo a \(h^n\); o que ainda está por ser adicionado é que existe um \(h^n\) do tipo postulado para todo \(\epsilon\), por menor que seja. Se incluirmos essa ideia em nossa suposição, nosso postulado de indução torna-se a hipótese de que existe um limite para a frequência relativa que não difere muito do valor observado. |

If we enter now into a closer analysis of this assumption, one thing needs no further demonstration: the formula given is not a tautology. There is indeed no logical necessity that \(h^s\) remains within the interval \(h^n\) \(\pm\) \(\epsilon\); we may easily imagine that this does not take place. |

Se entrarmos agora em uma análise mais detalhada dessa suposição, uma coisa não precisa de mais demonstração: a fórmula dada não é uma tautologia. De fato, não há necessidade lógica de que \(h^s\) permaneça dentro do intervalo \(h^n\) \(\pm\) \(\epsilon\); podemos facilmente imaginar que isso não ocorre. |

The non-tautological character of induction has been known a long time; Bacon had already emphasized that it is just this character to which the importance of induction is due. If inductive inference can teach us something new, in opposition to deductive inference, this is because it is not a tautology. This useful quality has, however, become the center of the epistemological difficulties of induction. It was David Hume who first attacked the principle from this side; he pointed out that the apparent constraint of the inductive inference, although submitted to by everybody, could not be justified. We believe in induction; we even cannot get rid of the belief when we know the impossibility of a logical demonstration of the validity of inductive inference; but as logicians we must admit that this belief is a deception — such is the result of Hume’s criticism. We may summarize his objections in two statements: |

O caráter não tautológico da indução já é conhecido há muito tempo; Bacon já havia enfatizado que é justamente a esse caráter que se deve a importância da indução. Se a inferência indutiva pode nos ensinar algo novo, em oposição à inferência dedutiva, é porque ela não é uma tautologia. Essa qualidade útil, no entanto, tornou-se o centro das dificuldades epistemológicas da indução. Foi David Hume quem primeiro atacou o princípio por este lado; salientou que a aparente coerção da inferência indutiva, embora aceita por todos, não podia ser justificada. Acreditamos na indução; nem mesmo podemos nos livrar da crença quando sabemos da impossibilidade de uma demonstração lógica da validade da inferência indutiva; mas como lógicos devemos admitir que essa crença é um engano — tal é o resultado da crítica de Hume. Podemos resumir suas objeções em duas declarações: |

1. We have no logical demonstration for the validity of inductive inference. |

1. Não temos demonstração lógica para a validade da inferência indutiva. |

2. There is no demonstration a posteriori for the inductive inference; any such demonstration would presuppose the very principle which it is to demonstrate. |

2. Não há demonstração a posteriori para a inferência indutiva; qualquer demonstração desse tipo pressupõe o próprio princípio que deve demonstrar. |

These two pillars of Hume’s criticism of the principle of induction have stood unshaken for two centuries, and I think they will stand as long as there is a scientific philosophy. |

Esses dois pilares da crítica de Hume ao princípio da indução permaneceram inabaláveis por dois séculos, e acho que permanecerão enquanto houver uma filosofia científica. |

In spite of the deep impression Hume’s discovery made on his contemporaries, its relevance was not sufficiently noticed in the subsequent intellectual development. I do not refer here to the speculative metaphysicians which the nineteenth century presented to us so copiously, especially in Germany; we need not be surprised that they did not pay any attention to objections which so soberly demonstrated the limitations of human reason. But empiricists, and even mathematical logicians, were no better in this respect. It is astonishing to see how clear-minded logicians, like John Stuart Mill, or Whewell, or Boole, or Venn, in writing about the problem of induction, disregarded the bearing of Hume’s objections; they did not realize that any logic of science remains a failure so long as we have no theory of induction which is not exposed to Hume’s criticism. It was without doubt their logical apriorism which prevented them from admitting the unsatisfactory character of their own theories of induction. But it remains incomprehensible that their empiricist principles did not lead them to attribute a higher weight to Hume’s criticism. |

Apesar da profunda impressão que a descoberta de Hume causou em seus contemporâneos, sua relevância não foi suficientemente notada no desenvolvimento intelectual subsequente. Não me refiro aqui aos metafísicos especulativos que o século XIX nos legou tão abundantemente, especialmente na Alemanha; não devemos nos surpreender que eles não tenham dado atenção às objeções que tão sobriamente demonstravam as limitações da razão humana. Mas os empiristas, e mesmo os lógicos matemáticos, não eram melhores nesse aspecto. É surpreendente ver como lógicos de mente clara, como John Stuart Mill, ou Whewell, ou Boole, ou Venn, ao escrever sobre o problema da indução, desconsideraram o alcance das objeções de Hume; eles não perceberam que qualquer lógica da ciência permanece um fracasso enquanto não tivermos nenhuma teoria da indução que não seja exposta à crítica de Hume. Foi sem dúvida o apriorismo lógico deles que os impediu de admitir o caráter insatisfatório de suas próprias teorias da indução. Mas permanece incompreensível que seus princípios empiristas não os tenham levado a atribuir um peso maior à crítica de Hume. |

It has been with the rise of the formalistic interpretation of logic in the last few decades that the full weight of Hume’s objections has been once more realized. The demands for logical rigor have increased, and the blank in the chain of scientific inferences, indicated by Hume, could no longer be overlooked. The attempt made by modem positivists to establish knowledge as a system of absolute certainty found an insurmountable barrier in the problem of induction. In this situation an expedient has been proposed which cannot be regarded otherwise than as an act of despair. |

Foi com o surgimento da interpretação formalista da lógica nas últimas décadas que todo o peso das objeções de Hume foi mais uma vez percebido. As exigências de rigor lógico aumentaram, e o vazio na cadeia de inferências científicas, indicado por Hume, não poderia mais passar despercebido. A tentativa dos positivistas modernos de estabelecer o conhecimento como um sistema de certeza absoluta encontrou uma barreira intransponível no problema da indução. Nesta situação foi proposto um expediente que não pode ser considerado senão um ato de desespero. |

The remedy was sought in the principle of retrogression. We remember the role this principle played in the truth theory of the meaning of indirect sentences (§7); positivists who had already tried to carry through the principle within this domain now made the attempt to apply it to the solution of the problem of induction. They asked: Under what conditions do we apply the inductive principle in order to infer a new statement? They gave the true answer: We apply it when a number of observations is made which concern events of a homogeneous type and which furnish a frequency \(h^n\) for a determinate kind of events among them. What is inferred from this? You suppose, they said, that you are able to infer from this a similar future prolongation of the series; but, according to the principle of retrogression, this “prediction of the future” cannot have a meaning which is more than a repetition of the premises of the inference — it means nothing but stating, “There was a series of observations of such and such kind.” The meaning of a statement about the future is a statement about the past — this is what furnishes the application of the principle of retrogression to inductive inference. |

O remédio foi buscado no princípio do retrogressão. Recordamos o papel que este princípio desempenhou na teoria da verdade do significado das frases indiretas (§7); os positivistas que já haviam tentado estabelecer o princípio dentro desse domínio agora tentavam aplicá-lo à solução do problema da indução. Eles perguntaram: em que condições aplicamos o princípio indutivo para inferir uma nova afirmação? Eles deram a resposta verdadeira: nós a aplicamos quando um número de observações é feito que diz respeito a eventos de um tipo homogêneo e que fornecem uma frequência \(h^n\) para um tipo determinado de eventos entre eles. O que é inferido disso? Você supõe, eles disseram, que você pode inferir disso um prolongamento futuro semelhante da série; mas, de acordo com o princípio da retrogressão, essa “previsão do futuro” não pode ter um significado que seja mais do que uma repetição das premissas da inferência — não significa nada além de afirmar: “houve uma série de observações de tal e tal tipo.” O significado de uma afirmação sobre o futuro é uma afirmação sobre o passado — é isso que fornece a aplicação do princípio de retrogressão à inferência indutiva. |

I do not think that such reasoning would convince any sound intellect. Far from considering it as an analysis of science, I should regard such an interpretation of induction rather as an act of intellectual suicide. The discrepancy between actual thinking and the epistemological result so obtained is too obvious. The only thing to be inferred from this demonstration is that the principle of retrogression does not hold if we want to keep our epistemological construction in correspondence with the actual procedure of science. We know pretty well that science wants to foresee the future; and, if anybody tells us that “foreseeing the future” means “reporting the past,” we can only answer that epistemology should be something other than a play with words. |

Não creio que tal raciocínio convença qualquer intelecto sadio. Longe de considerá-la uma análise da ciência, devo considerar tal interpretação da indução antes como um ato de suicídio intelectual. A discrepância entre o pensamento real e o resultado epistemológico assim obtido é muito óbvia. A única coisa a ser inferida dessa demonstração é que o princípio do retrogressão não se sustenta se quisermos manter nossa construção epistemológica em correspondência com o procedimento real da ciência. Sabemos muito bem que a ciência quer prever o futuro; e, se alguém nos diz que “prever o futuro” significa “relatar o passado”, só podemos responder que a epistemologia deveria ser outra coisa que um mero jogo de palavras. |

It is the postulate of utilizability which excludes the interpretation of the inductive inference in terms of the principle of retrogression. If scientific statements are to be utilizable for actions, they must pass beyond the statements on which they are based; they must concern future events and not those of the past alone. To prepare for action presupposes — besides a volitional decision concerning the aim of the action — some knowledge about the future. If we were to give a correct form to the reasoning described, it would amount to maintaining that there is no demonstrable knowledge about the future. This was surely the idea of Hume. Instead of any pseudo-solution of the problem of induction, we should then simply confine ourselves to the repetition of Hume’s result and admit that the postulate of utilizability cannot be satisfied. The truth theory of meaning leads to a Humean skepticism — this is what follows from the course of the argument. |

É o postulado da usabilidade que exclui a interpretação da inferência indutiva em termos do princípio do retrogressão. Se as declarações científicas devem ser utilizadas para ações, elas devem ir além das declarações nas quais se baseiam; elas devem dizer respeito a eventos futuros e não apenas aos do passado. Preparar-se para a ação pressupõe — além de uma decisão volitiva sobre o objetivo da ação — algum conhecimento sobre o futuro. Se dermos uma forma correta ao raciocínio descrito, isso equivaleria a sustentar que não há conhecimento demonstrável sobre o futuro. Esta foi certamente a ideia de Hume. Em vez de qualquer pseudo-solução do problema da indução, devemos simplesmente nos limitar à repetição do resultado de Hume e admitir que o postulado da usabilidade não pode ser satisfeito. A teoria da verdade do significado leva a um ceticismo humeano — é o que se segue do curso do argumento. |

It was the intention of modern positivism to restore knowledge to absolute certainty; what was proposed with the formalistic interpretation of logic was nothing other than a resumption of the program of Descartes. The great founder of rationalism wanted to reject all knowledge which could not be considered as absolutely reliable; it was the same principle which led modern logicians to a denial of a priori principles. It is true that this principle led Descartes himself to apriorism; but this difference may be considered as a difference in the stage of historical development — his rationalistic apriorism was to perform the same function of sweeping away all untenable scientific claims as was intended by the later struggle against a priori principles. The refusal to admit any kind of material logic — i.e., any logic furnishing information about some “matter” — springs from the Cartesian source: It is the ineradicable desire of absolutely certain knowledge which stands behind both the rationalism of Descartes and the logicism of positivists. |

Era a intenção do positivismo moderno restaurar o conhecimento à certeza absoluta; o que se propunha com a interpretação formalista da lógica nada mais era do que uma retomada do programa de Descartes. O grande fundador do racionalismo queria rejeitar todo conhecimento que não pudesse ser considerado absolutamente confiável; foi o mesmo princípio que levou os lógicos modernos a uma negação da princípios a priori. É verdade que esse princípio levou o próprio Descartes ao apriorismo; mas essa diferença pode ser considerada como uma diferença no estágio do desenvolvimento histórico — seu apriorismo racionalista deveria desempenhar a mesma função de varrer todas as alegações científicas insustentáveis como pretendia a luta posterior contra princípios a priori. A recusa em admitir qualquer tipo de lógica material — isto é, qualquer lógica que forneça informações sobre alguma “matéria” — brota da fonte cartesiana: é o desejo inerradicável de um conhecimento absolutamente certo que está por trás tanto do racionalismo de Descartes quanto do logicismo dos positivistas. |

The answer given to Descartes by Hume holds as well for modern positivism. There is no certainty in any knowledge about the world because knowledge of the world involves predictions of the future. The ideal of absolutely certain knowledge leads into skepticism — it is preferable to admit this than to indulge in reveries about a priori knowledge. Only a lack of intellectual radicalism could prevent the rationalists from seeing this; modem positivists should have the courage to draw this skeptical conclusion, to trace the ideal of absolute certainty to its inescapable implications. |

A resposta dada a Descartes por Hume vale também para o positivismo moderno. Não há certeza em qualquer conhecimento sobre o mundo porque o conhecimento do mundo envolve previsões do futuro. O ideal do conhecimento absolutamente certo leva ao ceticismo –– é preferível admitir isso do que se entregar a devaneios sobre o conhecimento a priori. Somente a falta de radicalismo intelectual poderia impedir os racionalistas de ver isso; os positivistas modernos deveriam ter a coragem de traçar essa conclusão cética, de traçar o ideal de certeza absoluta até suas implicações inescapáveis. |

However, instead of such a strict disavowal of the predictive aim of science, there is in modern positivism a tendency to evade this alternative and to underrate the relevance of Hume’s skeptical objections. It is true that Hume himself is not guiltless in this respect. He is not ready to realize the tragic consequences of his criticism; his theory of inductive belief as a habit — which surely cannot be called a solution of the problem — is put forward with the intention of veiling the gap pointed out by him between experience and prediction. He is not alarmed by his discovery; he does not realize that, if there is no escape from the dilemma pointed out by him, science might as well not be continued — there is no use for a system of predictions if it is nothing but a ridiculous self-delusion. There are modern positivists who do not realize this either. They talk about the formation of scientific theories, but they do not see that, if there is no justification for the inductive inference, the working procedure of science sinks to the level of a game and can no longer be justified by the applicability of its results for the purpose of actions. It was the intention of Kant’s synthetic a priori to secure this working procedure against Hume’s doubts; we know today that Kant’s attempt at rescue failed. We owe this critical result to the establishment of the formalistic conception of logic. If, however, we should not be able to find an answer to Hume’s objections within the frame of logistic formalism, we ought to admit frankly that the antimetaphysical version of philosophy led to the renunciation of any justification of the predictive methods of science — led to a definitive failure of scientific philosophy. |

No entanto, em vez de uma negação tão estrita do objetivo preditivo da ciência, há no positivismo moderno uma tendência a fugir dessa alternativa e subestimar a relevância das objeções céticas de Hume. É verdade que o próprio Hume não é inocente a esse respeito. Ele não está pronto para perceber as consequências trágicas de sua crítica; sua teoria da crença indutiva como hábito — que certamente não pode ser chamada de solução do problema — é apresentada com a intenção de velar a lacuna apontada por ele entre experiência e previsão. Ele não está alarmado com sua descoberta; ele não percebe que, se não há como escapar do dilema apontado por ele, a ciência poderia muito bem não continuar — não adianta um sistema de previsões se não for nada além de uma ridícula autoilusão. Há positivistas modernos que também não percebem isso. Eles falam sobre a formação de teorias científicas, mas não veem que, se não houver justificativa para a inferência indutiva, o procedimento de trabalho da ciência cai ao nível de um jogo e não pode mais ser justificado pela aplicabilidade de seus resultados para fins de ações. A intenção do sintético a priori de Kant era proteger esse procedimento de trabalho contra as dúvidas de Hume; sabemos hoje que a tentativa de resgate de Kant falhou. Devemos esse resultado crítico ao estabelecimento da concepção formalista de lógica. Se, no entanto, não formos capazes de encontrar uma resposta para as objeções de Hume dentro do quadro do formalismo logístico, devemos admitir francamente que a versão antimetafísica da filosofia levou à renúncia de qualquer justificação dos métodos preditivos da ciência – levou a um fracasso definitivo da filosofia científica. |

Inductive inference cannot be dispensed with because we need it for the purpose of action. To deem the inductive assumption unworthy of the assent of a philosopher, to keep a distinguished reserve, and to meet with a condescending smile the attempts of other people to bridge the gap between experience and prediction is cheap selfdeceit; at the very moment when the apostles of such a higher philosophy leave the field of theoretical discussion and pass to the simplest actions of daily life, they follow the inductive principle as surely as does every earth-bound mind. In any action there are various means to the realization of our aim; we have to make a choice, and we decide in accordance with the inductive principle. Although there is no means which will produce with certainty the desired effect, we do not leave the choice to chance but prefer the means indicated by the principle of induction. If we sit at the wheel of a car and want to turn the car to the right, why do we turn the wheel to the right ? There is no certainty that the car will follow the wheel; there are indeed cars which do not always so behave. Such cases are fortunately exceptions. But if we should not regard the inductive prescription and consider the effect of a turn of the wheel as entirely unknown to us, we might turn it to the left as well. I do not say this to suggest such an attempt; the effects of skeptical philosophy applied in motor traffic would be rather unpleasant. But I should say a philosopher who is to put aside his principles any time he steers a motorcar is a bad philosopher. |

A inferência indutiva não pode ser dispensada porque precisamos dela para fins de ação. Considerar a suposição indutiva indigna do assentimento de um filósofo, manter uma distinta reserva e enfrentar com um sorriso condescendente as tentativas de outras pessoas de preencher a lacuna entre experiência e predição é um autoengano barato; no exato momento em que os apóstolos de uma filosofia tão elevada deixam o campo da discussão teórica e passam para as ações mais simples da vida diária, eles seguem o princípio indutivo com a mesma certeza de qualquer mente ligada à terra. Em qualquer ação existem vários meios para a realização de nosso objetivo; temos que fazer uma escolha e decidimos de acordo com o princípio indutivo. Embora não haja meios que produzam com certeza o efeito desejado, não deixamos a escolha ao acaso, mas preferimos os meios indicados pelo princípio da indução. Se nos sentamos ao volante de um carro e queremos virar o carro para a direita, por que viramos o volante para a direita? Não há certeza de que o carro seguirá o volante; há de facto carros que nem sempre se comportam assim. Esses casos são, felizmente, exceções. Mas se não considerarmos a prescrição indutiva e considerarmos o efeito de um giro da roda como inteiramente desconhecido para nós, poderíamos girá-lo também para a esquerda. Não digo isso para sugerir tal tentativa; os efeitos da filosofia cética aplicada ao tráfego motorizado seriam bastante desagradáveis. Mas devo dizer que um filósofo que deixa de lado seus princípios sempre que dirige um automóvel é um mau filósofo. |

It is no justification of inductive belief to show that it is a habit. It is a habit; but the question is whether it is a good habit, where “good” is to mean “useful for the purpose of actions directed to future events.” If a person tells me that Socrates is a man, and that all men are mortal, I have the habit of believing that Socrates is mortal. I know, however, that this is a good habit. If anyone had the habit of believing in such a case that Socrates is not mortal, we could demonstrate to him that this was a bad habit. The analogous question must be raised for inductive inference. If we should not be able to demonstrate that it is a good habit, we should either cease using it or admit frankly that our philosophy is a failure. |

Não é justificação da crença indutiva mostrar que é um hábito. É um hábito; mas a questão é se é um bom hábito, onde “bom” significa “útil para o propósito de ações direcionadas a eventos futuros”. Tenho o hábito de acreditar que Sócrates é mortal. Sei, porém, que esse é um bom hábito. Se alguém teve o hábito de acreditar em tal caso que Sócrates não é mortal, poderíamos demonstrar a ele que isso era um mau hábito. A questão análoga deve ser levantada para a inferência indutiva. Se não formos capazes de demonstrar que é um bom hábito, devemos parar de usá-lo ou admitir francamente que nossa filosofia é um fracasso. |

Science proceeds by induction and not by tautological transformations of reports. Bacon is right about Aristotle; but the novum organon needs a justification as good as that of the organon. Hume’s criticism was the heaviest blow against empiricism; if we do not want to dupe our consciousness of this by means of the narcotic drug of aprioristic rationalism, or the soporific of skepticism, we must find a defense for the inductive inference which holds as well as does the formalistic justification of deductive logic. |

A ciência procede por indução e não por transformações tautológicas de relatos. Bacon está certo sobre Aristóteles; mas o novum organon precisa de uma justificativa tão boa quanto a do organon. A crítica de Hume foi o golpe mais pesado contra o empirismo; se não quisermos enganar nossa consciência disso por meio da droga narcótica do racionalismo apriorístico, ou do soporífero do ceticismo, devemos encontrar uma defesa para a inferência indutiva que vale tanto quanto a justificação formalista da lógica dedutiva. |

Originalmente publicado em H. Reichenbach (1938), Experience and prediction: an analysis of the foundations and the structure of knowledge. ↩︎

Arquipélago Filosófico, Vol. 2, No. 2 (2026), e-002

ISSN 3086-1136

Informações do Artigo

Artigo: Hans Reichenbach, § 38 O problema da indução

Autor(es): Arquipélago

Data: 19 Jan 2026

DOI: -

Revista: -

Volume: -

Número: -

Páginas: -

ISSN: -

Citação BibTeX

Leia mais

Bertrand Russell, Conhecimento por ‘experiência direta’ e conhecimento por descrição

Este texto clássico de Russell constitui o capítulo 5 de seu livro de introdução à filosofia, The problems of philosophy (1912) e baseia-se no texto publicado em 1910 nos Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. Trata-se de um escrito fundamental da epistemologia e da filosofia da linguagem contemporânea, que vem sendo

Ludwik Fleck, Algumas características específicas do pensamento médico

O texto a seguir é uma tradução de uma palestra originalmente proferida em polonês e publicada em 1927 no Archiwum Historji i Filozofji Medycyny. Foi traduzido por Kariel Antonio Giarolo (IFRN) a partir de uma versão em inglês publicada no livro Cognition and fact: materials on Ludwik Fleck, editado por

Daniel Brudney, Quatro tipos de abordagem filosófica

O texto a seguir foi extraído do livro Marx’s attempt to leave philosophy, de Daniel Brudney (Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp. 77-80). O texto foi traduzido por Felipe Taufer (Univ. Caxias do Sul) e pode ser útil como um material didático de introdução à filosofia. [...] Deixe-me esboçar brevemente quatro

Frank Thomas Sautter, Introdução às Redes Dialéticas

Frank Thomas Sautter é professor titular da Universidade Federal de Santa Maria. Tem experiência na área de Filosofia, com ênfase em Lógica. Introdução Este texto é o primeiro de uma série de textos em que apresento e utilizo as Redes Dialéticas, uma ferramente gráfica para a anotação de argumentação. “Argumentação”